Around 5,000 British people convert to Islam every year – and most of them are women. Six of them talk about prejudice, peace and praying in car parks

Ioni Sullivan, local authority worker, 37, East Sussex

I'm married to a Muslim and have two children. We live in Lewes, where I'm probably the only hijabi in the village.

I was born and raised in a middle-class, left-leaning, atheist family; my father was a professor, my mother a teacher. When I finished my MPhil at Cambridge in 2000, I worked in Egypt, Jordan, Palestine and Israel. Back then, I had a fairly stereotypical view of Islam, but became impressed with the strength the people derived from their faith. Their lives sucked, yet nearly everyone I met seemed to approach their existence with a tranquillity and stability that stood in contrast to the world I'd left behind.

In 2001, I fell in love with and married a Jordanian from a fairly non-practising background. At first we lived a very western lifestyle, going out to bars and clubs, but around this time I started an Arabic course and picked up an English copy of the Qur'an. I found myself reading a book that claimed that the proof of God's existence was in the infinite beauty and balance of creation, not one that asked me to believe God walked the Earth in human form; I didn't need a priest to bless me or a sacred place to pray. Then I started looking into other Islamic practices that I'd dismissed as harsh: fasting, compulsory charity, the idea of modesty. I stopped seeing them as restrictions on personal freedom and realised they were ways of achieving self-control.

In my heart, I began to consider myself a Muslim, but didn't feel a need to shout about it; part of me was trying to avoid conflict with my family and friends. In the end it was the hijab that "outed" me to wider society: I began to feel I wasn't being true to myself if I didn't wear it. It caused some friction, and humour, too: people kept asking in hushed tones if I had cancer. But I've been pleasantly surprised at how little it has mattered in any meaningful relationship I have.

Anita Nayyar, social psychologist and gender equalities activist, 31, London

Anita Nayyar: 'One of the biggest challenges I face is the prohibition of women from the mosque.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

Anita Nayyar: 'One of the biggest challenges I face is the prohibition of women from the mosque.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

As an Anglo-Indian with Hindu grandparents who lived through the partition of India and Pakistan, and saw family shot by a Muslim gang, I was brought up with a fairly dim view of what it was to be Muslim.

I was a very religious Christian, involved in the church, and wanted to become a vicar. At 16, I opted for a secular college, which is where I made friends with Muslims. I was shocked by how normal they were, and how much I liked them. I started debates, initially to let them know what a terrible religion they followed, and I started to learn that it wasn't too different from Christianity. In fact, it seemed to make more sense. It took a year and a half before I got to the point of conversion, and I became a Muslim in 2000, aged 18. My mother was disappointed and my father quietly accepting. Other members of my family felt betrayed.

I used to wear a scarf, which can mean many things. It can be a signifier of one's faith, which is helpful when you don't wish to be chatted up or invited to drink. It can attract negative attention from people who stereotype "visibly" Muslim women as oppressed or terrorist. It can also get positive reactions from the Muslim community.

But people expect certain behaviour from a woman in a headscarf, and I started to wonder whether I was doing it for God or to fulfil the role of "the pious woman". In the end, not wearing the scarf has helped make my faith invisible again and allowed me to revisit my personal relationship with God.

One of the biggest challenges I face is the prohibition of women from the mosque. It's sad to go somewhere, ready to connect with a higher being, only to be asked to leave because women are not allowed. In the past, I have prayed in car parks, my office corridor and in a fried chicken shop. The irony is that while my workplace would feel it discriminatory to stop me praying, some mosques do not.

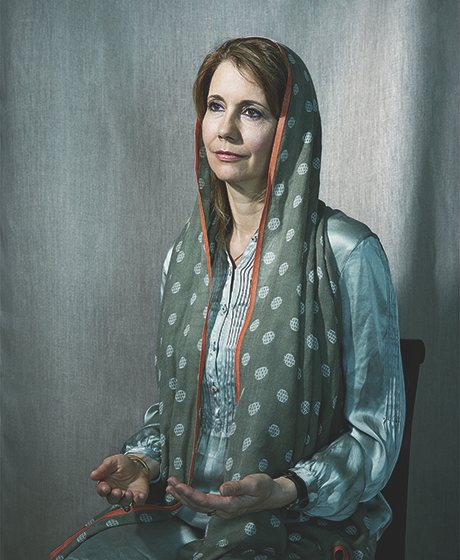

Dr Annie (Amina) Coxon, consultant physician and neurologist, 72, London

Dr Annie (Amina) Coxon: 'After 9/11, my relationship with my sister-in-law changed and I am no longer welcome in their home.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

Dr Annie (Amina) Coxon: 'After 9/11, my relationship with my sister-in-law changed and I am no longer welcome in their home.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

I'm English back to the Normans. I was brought up in the US and Egypt, before coming to boarding school in the UK at six, then doing medical training in London and the US. I've been married twice, have three stepchildren and five stepgrandchildren.

I converted 21 years ago. It was the result of a long search for a more spiritual alternative to Catholicism. Initially, I didn't consider Islam because of the negative image in the media. The conversion process was gradual and ultimately guided by the example of the mother of the current Sultan of Oman – one of my patients – and by a series of dreams.

My family were initially surprised, but accepted my conversion. After 9/11, however, my relationship with my sister-in-law changed and I am no longer welcome in their home. I have friends for whom my conversion is an accepted eccentricity, but I lost many superficial ones because of it.

When I converted, I was told by the imam that I should dress modestly, but didn't need to wear the hijab because I was already old. During Ramadan, however, I do warn patients that I'll look a bit different if they see me coming back from the mosque. The response has been fascination rather than repulsion.

I tried to join various Islamic communities: Turkish, Pakistani and Moroccan. I went to the Moroccan mosque for three years without one person greeting me or wishing me "Eid Mubarak". I had cancer and not one Muslim friend (except a very holy old man) came to pray with me in nine months of treatment. But these are small annoyances compared with what I've gained: serenity, wisdom and peace. I've now finally found my Muslim community and it is African.

Many Muslims come to London as immigrants. Their ethnic identity is tied to the mosque; they don't want white faces there. We are pioneers. There will be a time when white converts won't be seen as freaks.

Kristiane Backer, TV presenter, 47, London

Kristiane Backer: 'It has been a challenge transforming my TV work in line with my new-found values.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

Kristiane Backer: 'It has been a challenge transforming my TV work in line with my new-found values.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

I grew up in Germany in a Protestant but not terribly religious family, then in 1989 moved to London to present on MTV Europe. I interviewed everyone from Bob Geldof to David Bowie, worked hard and partied hard, but something was missing. At a moment of crisis, I was introduced to the cricketer Imran Khan. He gave me books on Islam and invited me to travel with him through Pakistan. Those trips opened a new dimension in my life, an awareness of spirituality. The Muslims I met touched me profoundly through their generosity, dignity and readiness to sacrifice for others. The more I read, the more Islam attracted me. I converted in 1995.

When the German media found out, a negative press campaign followed and within no time my contract was terminated. It was the end of my entertainment career. It has been a challenge transforming my TV work in line with my new-found values, but I am working on a Muslim culture and lifestyle show. I feel I have a bridging role to play between the Muslim heritage community and society at large.

Most Muslims marry young, often with the help of their families, but I converted at 30. When I was still single 10 years later, I decided to look online. There, I met and fell in love with a charming, Muslim-born TV producer from Morocco who lived in the US. We had a lot in common and married in 2006. But his interpretation of Islam became a way of controlling me: I was expected to give up my work, couldn't talk to men and even had to cut men out of old photographs. I should have stood up to him, because a lot of what he asked of me was not Islamic but cultural, but I wanted to make the marriage work. Insha Allah my future husband will be more trusting and focused on the inner values of Islam, rather than on outward restrictions.

I have no regrets. On the contrary: my life now has meaning and the void that I used to feel is filled with God, and that is priceless.

Andrea Chishti, reflexologist and secondary school teacher, 47, Watford

Andrea Chishti: 'Islam has strengthened my ethics and morals.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

Andrea Chishti: 'Islam has strengthened my ethics and morals.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

I have been happily married for 18 years to a British-born Muslim of Pakistani origins. We have a son, 11, and a daughter, eight.

Fida and I met at university in 1991. My interest in Islam was a symbiosis of love and intellectual ideas. Fida wanted a Muslim family, and by 1992 my interest in Islam had developed significantly, so I chose to convert. It took us three more years to get married. During that time, we battled things out, met friends and families, agreed on how to live together.

I grew up in Germany, in a household where religion did not play a prominent role. My father was an atheist, but my mother and my school left me with a conviction that spirituality was important. When I converted, my father thought it was crazy, but he liked my husband; even so, he bought me a little flat so I "could always come back". My mother was shocked, horrified even. We had a typical Pakistani wedding with Fida's large extended family, and I moved to another country, so it was a lot for her to deal with. His family were not all happy either, because they'd have preferred someone from a Muslim background.

I don't feel I need to dress differently. I don't feel I need to wear hijab in my daily life, but I am very comfortable wearing it in public when performing religious duties. I don't wear it also out of consideration for my mother, because it was a huge issue for her.

I was a sensible teenager. I didn't drink. I am a teacher. So, I didn't drop out of an old life to find a new one. But Islam has strengthened my ethics and morals, and given a good foundation for our family life.

You sometimes feel like a "trophy" because you are white. If you go to a gathering, everyone wants to help and teach you and take you under their wing, up to the point where I found it suffocating. But, mostly, a lot of conversion problems are human problems, women's problems.

Anonymous, software developer, East Midlands

'I feel my family will be disappointed, somewhat embarrassed and also scared that the world will treat me unfairly if I'm Muslim.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

'I feel my family will be disappointed, somewhat embarrassed and also scared that the world will treat me unfairly if I'm Muslim.' Photograph: Felicity McCabe for the Guardian

I was the talk of the student Islamic society when I became a Muslim: happy-go-lucky, trendy, outspoken me. After meeting Muslims at university, I'd become intrigued. I started studying Islam and taking heed of the Qur'an's teachings. Two years later, at 23, I took my shahadah (Islamic profession of faith).

The fact that my family were Sikhs intrigued many Muslims. I was handed many sisters' phone numbers and people wanted to meet me. Then it all went quiet: the sisters were too busy. It hurt; I was alone.

I am single, 26, and live at home with my family who are non-practising Punjabi Sikhs. My family and Sikh friends have yet to learn of my conversion, but I am not hiding my copies of the Qur'an. I want my family to see that I'm studying Islam with a fine-tooth comb, so they'll know I've made a well-informed decision; Islam has given me a sense of independence and serenity, I've become more accepting of what life throws at me and less competitive. But I feel they will be disappointed, somewhat embarrassed and also scared that the world will treat me unfairly if I'm Muslim.

Becoming a Muslim is not easy: people say hurtful things about your faith, and it's a struggle to fit in with pious-looking sisters who wear traditional Arabic dress. It's also hard to kiss goodbye to nights out in bars with friends. I loved to party; I still do. I take pride in my appearance: I wear makeup, dresses and heels. Initially, I went in all guns blazing and covered every inch of my body. I used to go to work in the hijab and remove it as I drove back into my home city. It was as if I was leading a double life and that became tiresome and stressful, so I stopped.

I would like to marry sooner rather than later, but how will I ever find a suitable husband? Most Muslims find mingling with women haram [forbidden by Islamic law]. Because I am not fully out in the open, Muslim men won't know I exist.

• This article was edited on 14 October 2013. Since the interviews, Kristiane Backer's personal circumstances have changed, and the piece has been changed to reflect this. Also, an additional, anonymous interviewee has been added at the end.

source http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/11/islam-converts-british-women-prejudice

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness

Sri lanka Muslims Web Portal Diversity and Inclusiveness

Great article!